Optimizing the DOM

A large and inefficient webpage structure (Document Object Model, or DOM) can significantly slow down your site and negatively impact Core Web Vitals metrics. Keeping it reasonably sized and highly efficient is crucial for the overall technical performance of your project and will influence the interaction response speed (INP metric).

In this text, you can look forward to insights gathered over many years of experience as a consultant on DOM. You'll discover why its overall size matters, how to easily measure it, and how to optimize the HTML structure for faster rendering.

Size Matters

The DOM, a tree structure of components, tends to grow rapidly in the real world of the web. Adding elements and nesting them in HTML is straightforward. Therefore, it's necessary to consciously restrain it.

The DOM is considered too large if it has too many elements or deep nesting. Google recommends a maximum of 1,400 elements.

This is quite strict, especially for larger sites like e-commerce or applications. From our experience, browsers handle 2,500 DOM elements quite swiftly.

Once the number of DOM elements exceeds this threshold, everything starts to complicate quickly. Naturally, the smaller and more efficient it is, the better.

Why Must the DOM Be Efficient?

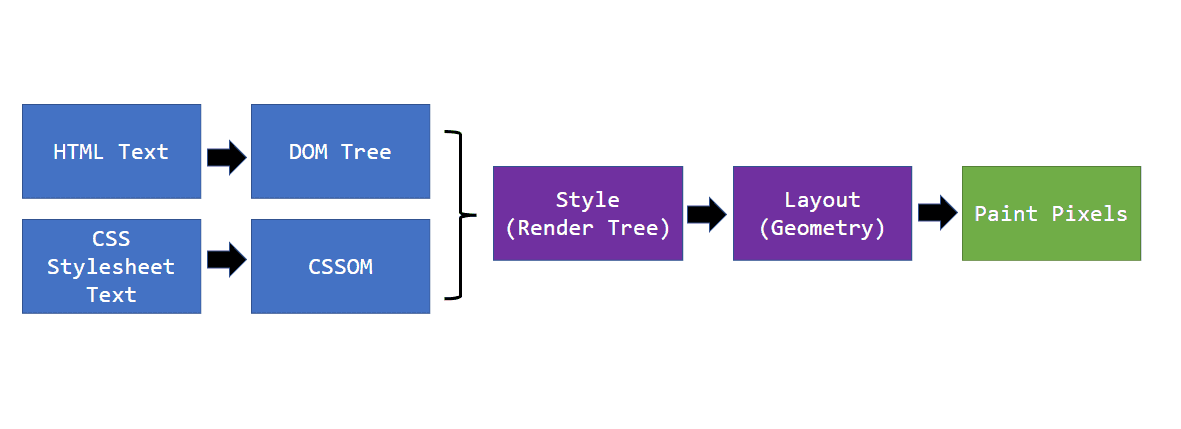

It's important to realize that HTML is initially just a string of structured text prepared by the browser. Ideally, this is constructed on the server, then downloaded to the browser where it is converted into a dynamic tree structure. This is called parsing.

Rendering process diagram. HTML is parsed into DOM. After combining with CSS, it moves to layout calculation and drawing on the screen.

Rendering process diagram. HTML is parsed into DOM. After combining with CSS, it moves to layout calculation and drawing on the screen.

But that's not all. DOM construction occurs at the beginning of the rendering process. The rendering process has several steps, so DOM inefficiency negatively affects everything.

-

On the server

The more complex the DOM, the more data and database queries. Assembling HTML takes longer, slowing down the TTFB metric. -

Transferring HTML to the browser

More data takes longer to transfer over the network, slowing metrics like FCP or LCP, i.e., loading speed. -

Parsing the HTML string and assembling the DOM

More elements take longer for the browser to convert into a tree structure. -

Applying styles and layout calculation

CSS selectors will be applied to more elements, prolonging layout calculation. -

Drawing on the screen

This phase is quite well optimized by the browser, but even here, large DOMs can cause problems. It depends on how CSS is handled. -

In every interaction

The DOM is dynamic and reacts to user input and JavaScript. A large DOM takes more time to reflect changes on the screen.

An efficient DOM reduces the strain on the entire rendering process and saves resources on the server side as well.

Info: Understanding rendering is key to a fast web. In our workshops, we show you how this fascinating mechanism works, step by step.

How to Test DOM Complexity?

There are several ways to find out where you stand:

Lighthouse Report

One of the Lighthouse tool reports provides the total number of DOM elements on a page, the maximum DOM depth, and the maximum number of nested elements.

Lighthouse tool output, as seen in our test run report details.

Lighthouse tool output, as seen in our test run report details.

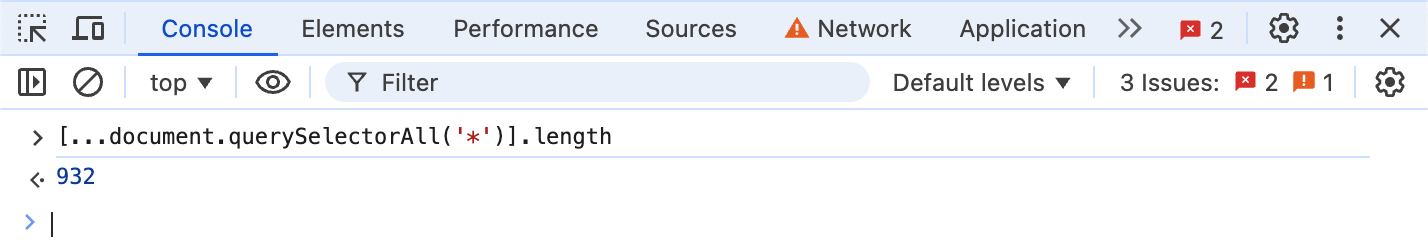

DevTools Console in the Browser

Another way is the DevTools console. With the page loaded, you simply run the following piece of code.

[...document.querySelectorAll('*')].length;

In Google Chrome, it looks like this:

The image shows the result of calling the script. There are 932 elements on the page.

The image shows the result of calling the script. There are 932 elements on the page.

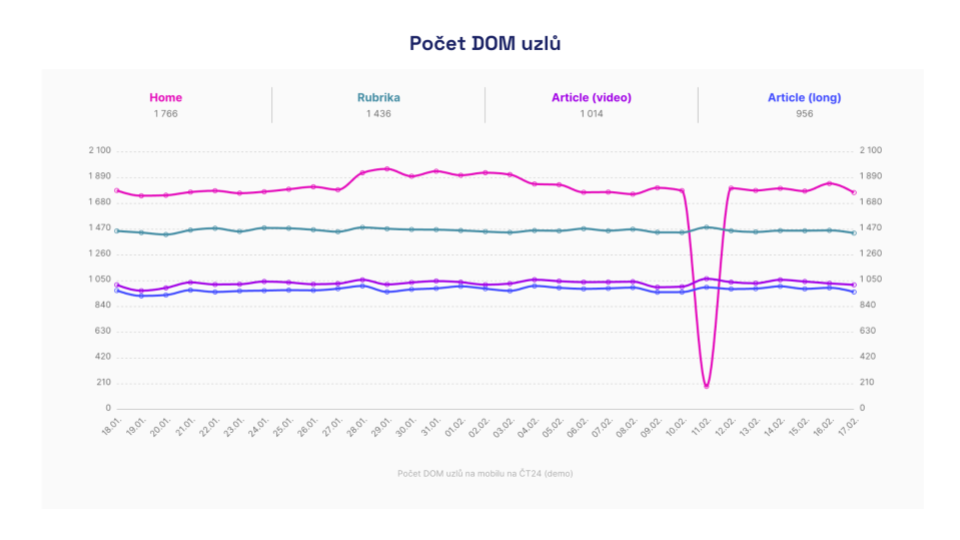

Number of DOM Elements in the "Technical" Report

In our PLUS monitoring, we track the number of DOM elements for every measured page. The graph shows how the web has developed over time.

Graph from the Technical report, showing the development of the number of DOM elements over time. It also shows how the monitoring detects an error on the homepage where the content was not rendering correctly.

Graph from the Technical report, showing the development of the number of DOM elements over time. It also shows how the monitoring detects an error on the homepage where the content was not rendering correctly.

DOM Optimization

Our recommendations will change your paradigm on HTML and DOM structure today. They may even shock you initially. When it comes to it, the DOM doesn't have to be large, even on really complex pages.

Delete Everything Not Needed in the Code at Load

The most efficient approach is to delete and lazy-load everything that doesn't need to be in the code. How do you know what to delete? Just ask yourself these questions:

-

Does the component have any significant informational value?

Robots often can't work with some components at all, such as forms and filters. Therefore, they don't need to be in the default code in their full structure. -

Is it purely a visual element?

Visual elements must be explained in code textually for machine information value. Examples are dynamic charts, maps. -

How much added value does the component have for the main content?

We often overload websites with various additional information. Examples include chats, side contact boxes, often entire sidebars, or footers. These often don't need to be in the default DOM. -

Is it specific only to one particular user?

If you delete such content, you significantly increase the likelihood of caching. Examples include user profile boxes and carts, recently visited products. -

Is the content duplicated in any component?

Such components unnecessarily inflate the DOM. Technically, duplication was once the only correct option for coders. This is no longer true with modern CSS. Alternatively, duplicated components can be generated and rendered with JavaScript when needed. A typical example is the main navigation, often coded twice. Once for mobile and once for desktop.

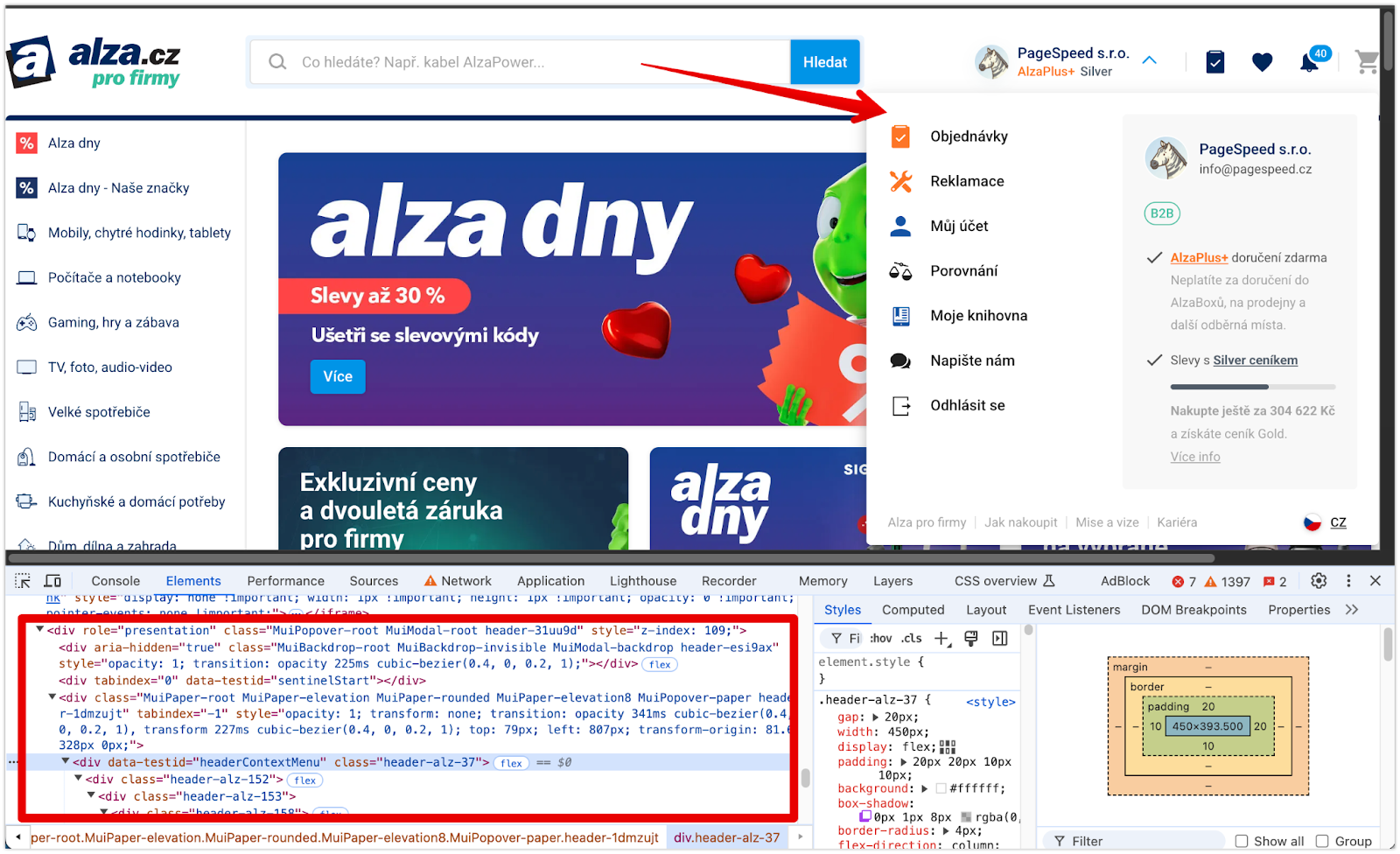

Example of a correct solution on alza.cz. The user menu appears in the DOM only after clicking the dropdown. It is removed again when closed.

Example of a correct solution on alza.cz. The user menu appears in the DOM only after clicking the dropdown. It is removed again when closed.

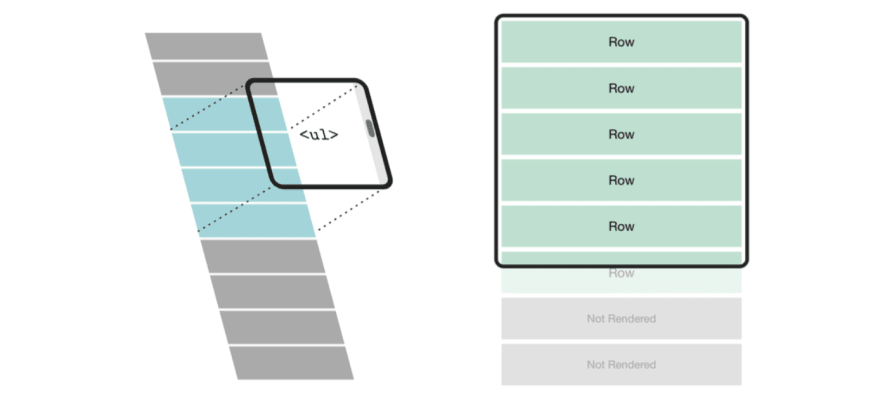

Simplify Components Until They Are Visible

Even if a component or its content is important for SEO or accessibility, it doesn't mean it has to be in full visual quality on initial render. Especially if the component is not visible in the first viewport.

How many components will the user actually see? Some are hidden behind interactions, like mega menus, others are seen after scrolling. Do you really need all components in HTML in their final form?

Optimization through splitting into a simple and rich component is particularly effective for elements repeated multiple times on a page. These are typically landing pages, product listings, or other offers, as shown in the image:

A more illustrative example of code follows, showing how to load a richer version of a component using the Intersection Observer:

import React from 'react';

import { useInView } from 'react-intersection-observer';

const Offer = ({ images, title }) => {

const { ref, inView, entry } = useInView();

return (

<article className="offer" ref={ref}>

<div className="gallery">

{!inView ? <Image data={images[0]} /> : <ImagesCarousel data={images} />}

<h3>{title}</h3>

</div>

</article>

);

};

Corresponding with the important content and resulting HTML, you'll find that the DOM skeleton can be relatively simple. Visual richness can be added on the frontend during the user's visit.

Optimize Long Lists and Tables

Browsers will always take time to render long lists or large tables. The content must be kept to a reasonable length. A listing with 100 products benefits no one.

Content must always be paginated, and if you want to use infinite scrolling, reuse DOM elements through virtual scrolling or remove already invisible items from the DOM and reserve space for them.

Simplify the Structure of Components

In UI, many components are often created. With today's modern HTML and CSS capabilities, we need fewer and fewer wrapping elements that serve only layout roles.

A typical example of waste is star ratings and unnecessary DOM expansion with separate "stars":

// Bad

<StarRating>

<SVGStar />

<SVGStar />

<SVGStar />

<SVGStar />

<SVGStar />

</StarRating>

A similar thing could be solved with a single element, setting the width and repeating background.

DOM Optimization: Practical Examples

As speed consultants, we've completed many successful DOM optimizations.

You can optimize the DOM on almost any project because it's often not directly monitored. Let's look at two optimizations that were very helpful and had a positive impact on the INP metric.

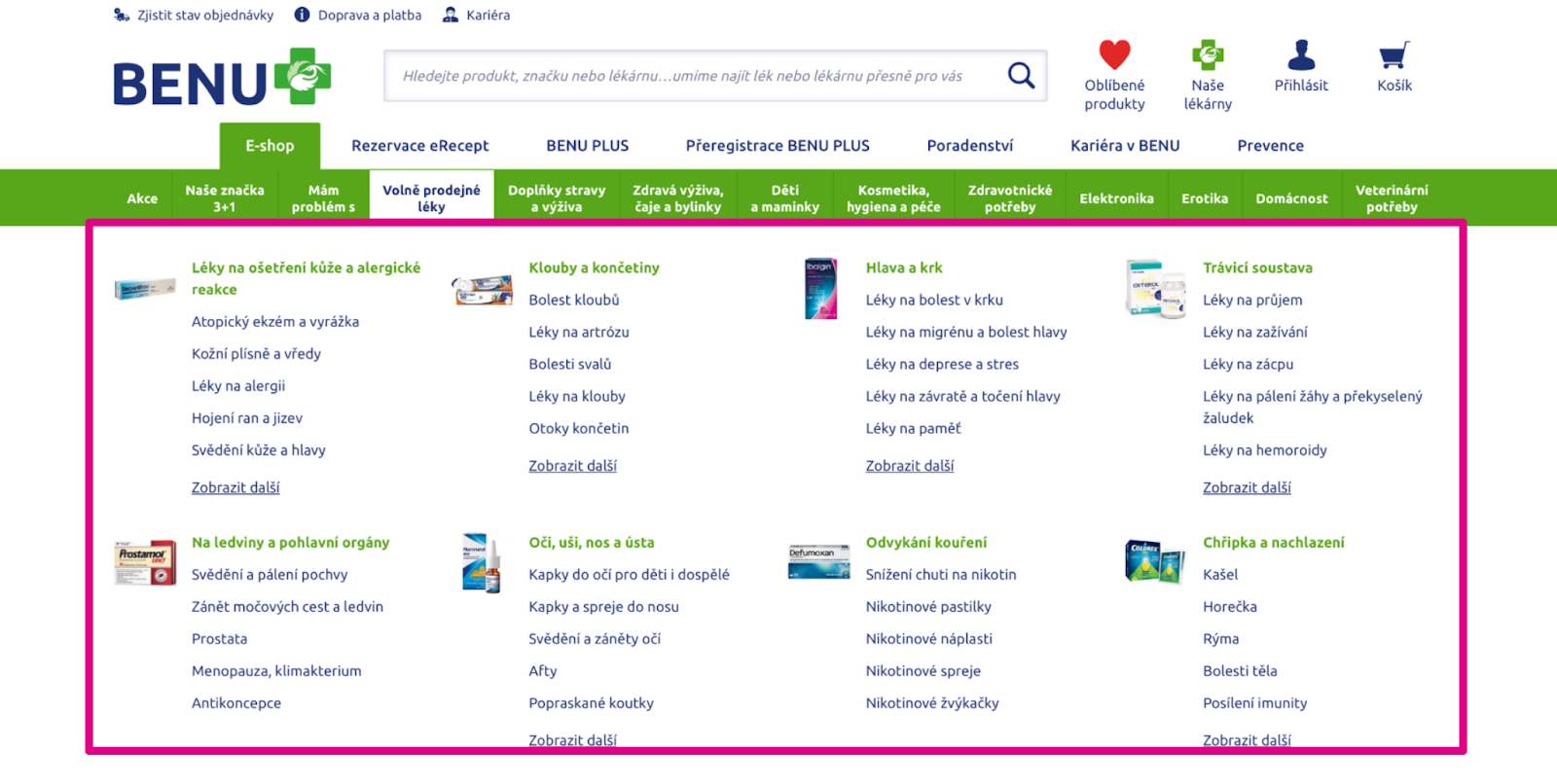

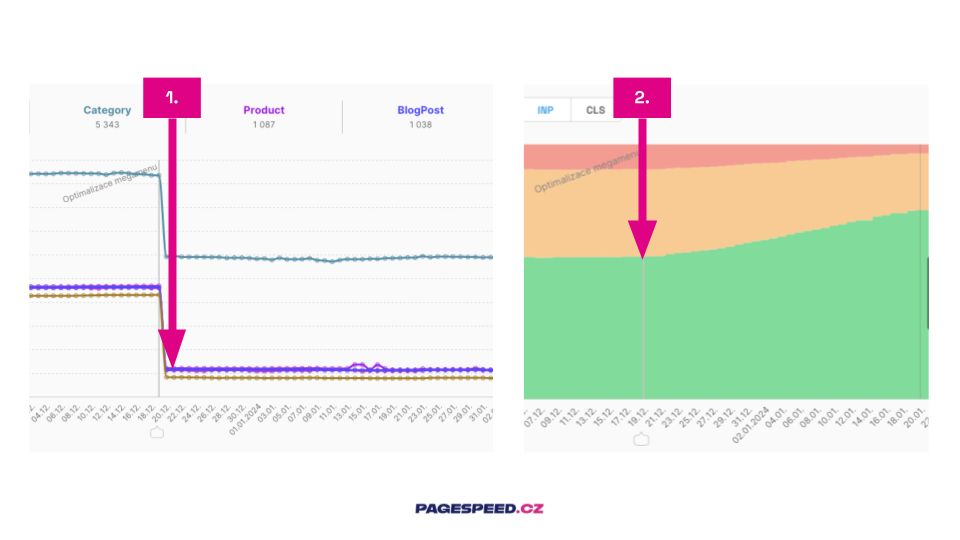

At Benu.cz, after consultations with SEO experts, we began optimizing the megamenu, which had nearly 3,000 elements on every page.

We focused optimization on reducing nested subcategories. Less important categories load lazily when the user needs them.

What do you see in the image?

- The impact of optimization visible on specific pages.

- On the entire domain, the distribution of the INP metric has changed since the optimization was implemented.

Placeholder Simplified Components

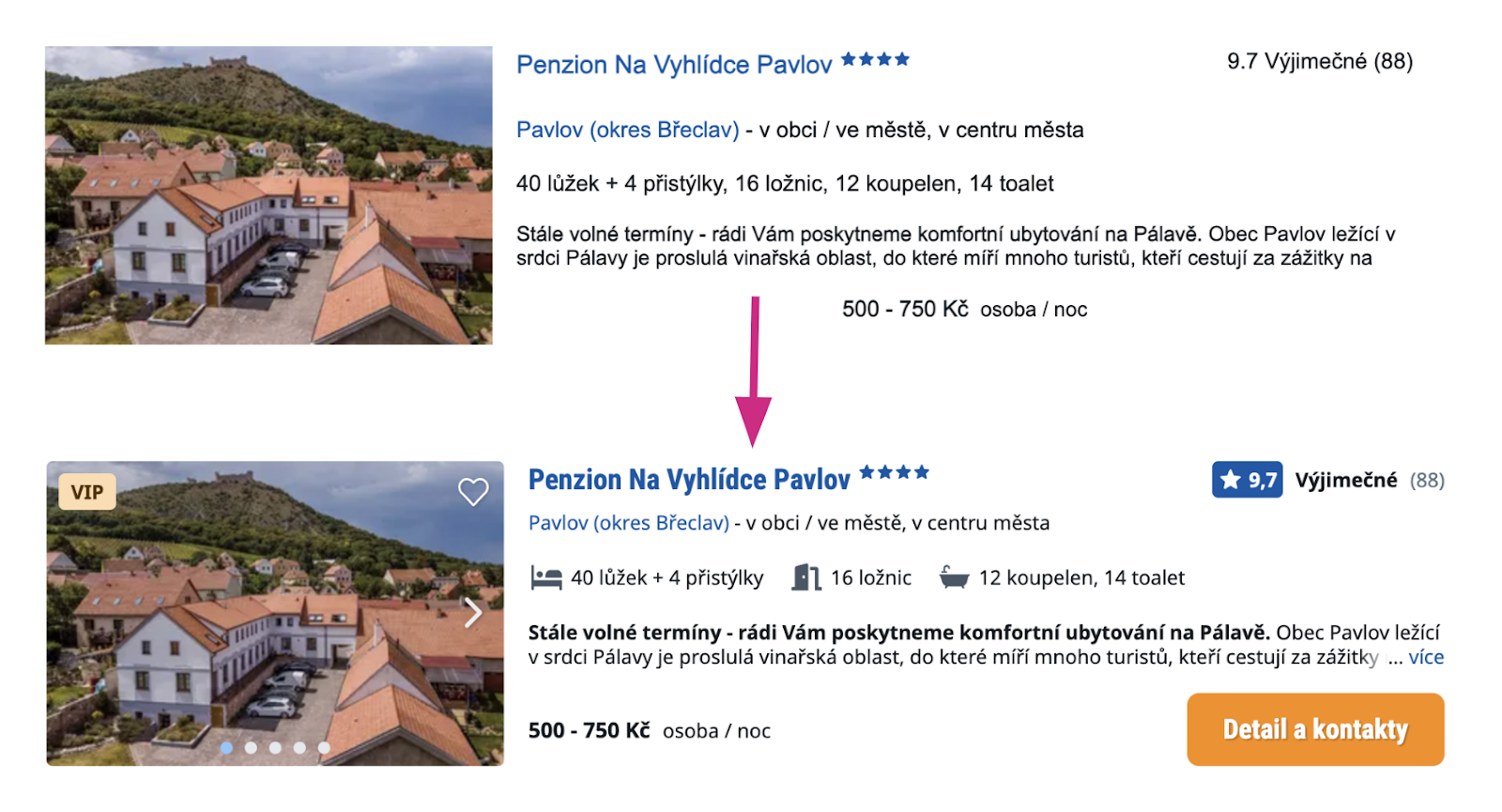

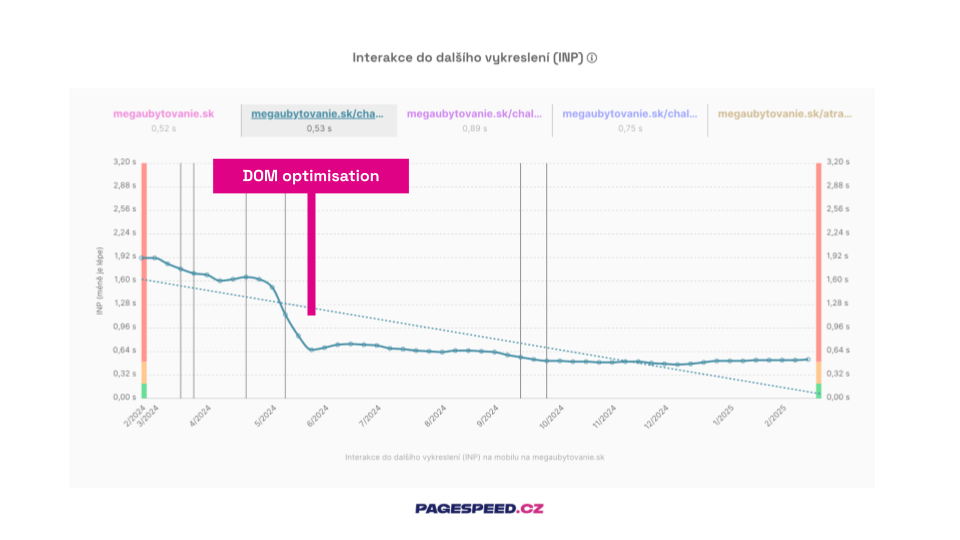

Megaubytovanie.sk is quite a content-rich project. It's like a "Czech-Slovak Booking." The site is built on the React framework and contains many directory blocks with offers.

We proposed using simplified components that provide only SEO-important data on page load. This state is visually hidden from the user. The "rich variant" activates when the component is displayed in the viewport.

Impact of DOM optimization on the INP metric for a page with offer listings.

Impact of DOM optimization on the INP metric for a page with offer listings.

Beware of CLS

When optimizing the DOM, pay attention to layout stability to ensure that faster rendering doesn't cause issues with the CLS metric.

Remember to always reserve space in the layout for lazily loaded and simplified components using placeholders. Pay special attention to removing components during scrolling.

Scrolling is not considered a user action for the CLS metric, so layout jumps at this moment would be heavily penalized.

Tip: A specific example of optimizing CLS with a placeholder can be found in the mini-case study on optimizing CLS on the Datart homepage.

Conclusion

The DOM is the skeleton; the DOM is everything.

Nowhere else can you achieve as much optimization at once as here. Therefore, give it the attention it deserves; it will undoubtedly pay off.

An efficient DOM increases content relevance, boosts indexability through TTFB, and speeds up your product. All of this leads to higher conversions.

Tagy:DOMOptimalizaceHTML